Good Morning!

I wanted to take my first bath of the season this weekend, the first bath since we moved into our flat earlier this year. Much of Sunday, I spent looking forward to it and talking about it. I had planned to prepare food to cook in the oven and take my bath in the meantime. But then dinner time came around and I ended up getting stressed about the logistics of it, the prospect of the bath suddenly dawning on me as a lot of effort, and I had yet to tidy the kitchen; and I was hungry and didn’t want to postpone eating any further. Taking a bath after dinner seemed silly to me, what with all the myths drilled into me as a child. The bath loomed over me as yet another to-do-list item, to be completed in the spirit of *self-care*. How silly, isn’t it, to think that taking a bath, the epitome of cosy me-time, has become for me an act of self-improvement akin to exercise or writing three full pages each morning. So I let go of the idea of the bath, enjoyed my dinner, settled on the sofa with my book. Liberated from the pressures of the bath, ridiculous as that sounds, I suddenly got up, turned on the tap, and added a delicious mix of sea salt and rosemary bath salts to the tub. I turned on a candle and my bath tub playlist and let myself sink into the steaming water.

The low sun, shining on the row of houses in this picture, have nothing to do really with this bathtub story. But they did catch my eye when I walked past. I adore this specific quality of autumnal afternoon sun, the rays powerful enough to warm you through to the bone, but only where they touch. So clear and warm, with the rippling clouds – after all, just like the water in my bath.

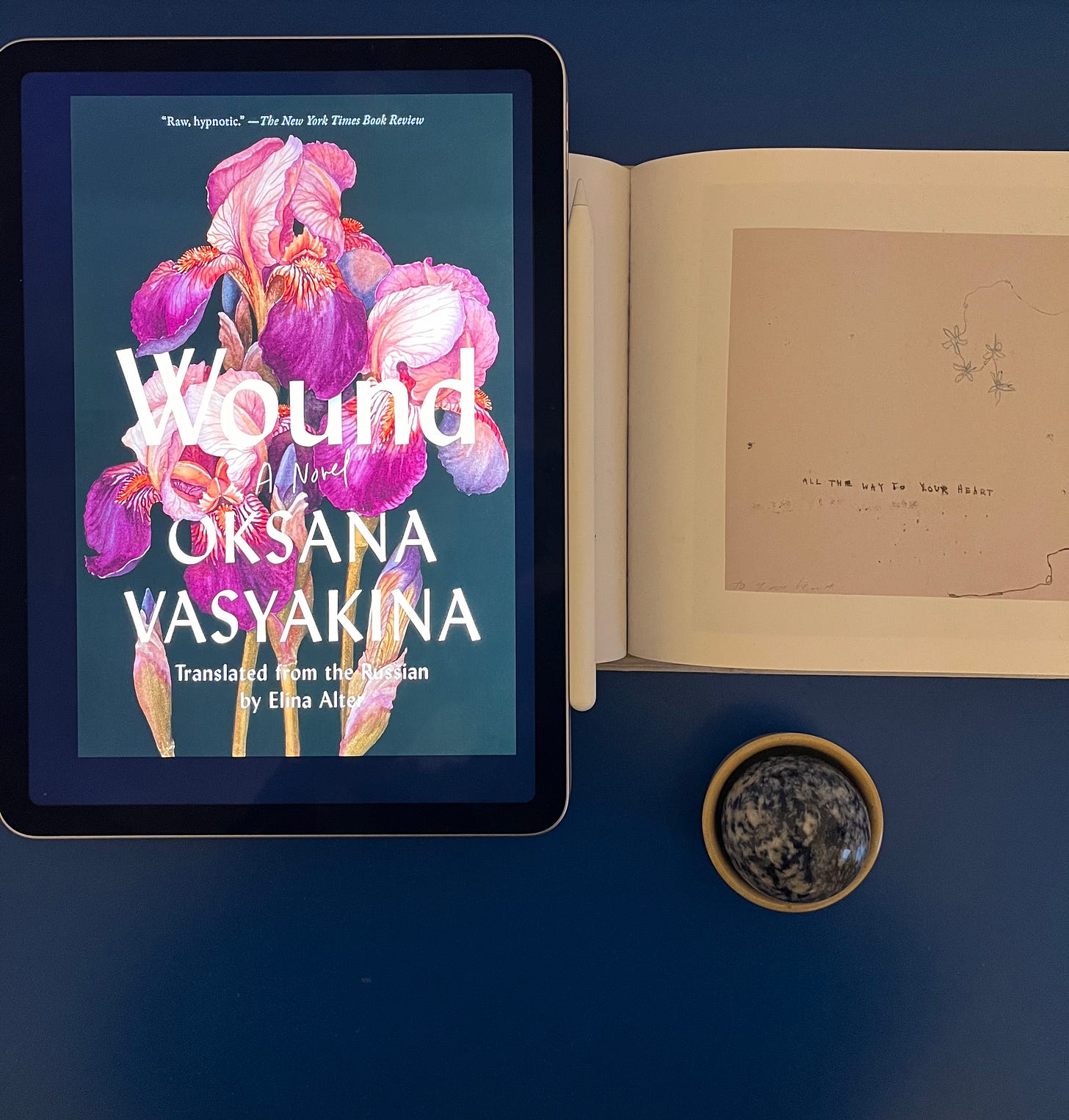

Review: Wound, by Oksana Vasyakina

Oksana Vasyakina’s novel Wound, translated from Russian by Elina Alter, is a deeply feeling, somewhat mythological autofictional jewel of queer literature. We read it this month in my queer fiction book club. This was a perfect book club book, because it has so many layers and such a complexly woven narrative, I very much enjoyed dissecting it with the group. Thank you to everyone who attended the November book club and whose thoughts feed into this review.

Wound is the story of a daughter whose mother dies painfully of breast cancer, of the daughter’s grief, of the complicated relationship between the two. It is also a story of the logistics of death. Oksana Vasyakina, the autofictional protagonist and narrator, must transport her mother’s ashes from Moscow to Ust-Ilimsk in Siberia. This journey spans the entire novel. The non-linear narrative takes the reader back to Vasyakina’s childhood, her adult life in Moscow, and time spent caring for her dying mother, all interspersed with anxious encounters with airport security. At the same time, the long journey takes her across the vastness of Russian landscapes, the precise descriptions of which made me finally get a grasp on the sheer size of Russia. (One book club attendant humblingly reminded me that it takes seven whole days to cross the country by Trans-Siberian rail).

Vasyakina excels at writing the mother, a deeply perplexing character whose mothering style I would probably classify as questionable, yet Vasyakina’s undying love for the mother and desire for her attention are inextricably linked with the author’s very existence. Their bodies, in sickness, in death, materially intertwined. The mother, who thinks her breast cancer stems from a dried, left-over droplet of milk; the daughter, whose physical reaction to this loss manifests in acute vulvitis and who finally finds peace in the (in my view, deeply intrusive and disturbing) realisation that part of her umbilical cord had never fallen off but instead has grown embedded in her belly button, hard to the touch.

In order to do this, I have to say you to you and address you as an equal elder. And you can look at me, too. Look at me.

Finally, it is the queerness of the genre, narrative infused with poetry, essay, and literary reflection, that lit the novel afire. Up until the last pages, Vasyakina does not address her mother, until finally, it is as if she turns away from the reader and towards the mother, she says ‘you’. She demands the mother’s gaze in gazing at her herself.

Thanks for reading, see you next time!